Chandrayaan-3’s measurements of sulfur open the doors for lunar science and exploration

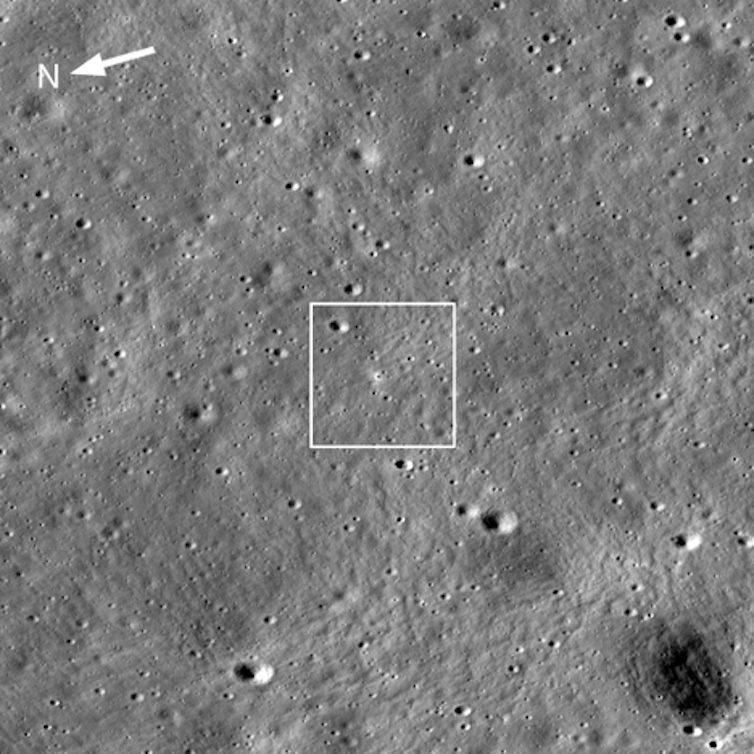

In an exciting milestone for lunar scientists around the globe, India’s Chandrayaan-3 lander touched down 375 miles (600 km) from the south pole of the Moon on Aug. 23, 2023

Estimated reading time: 14 minutes

Jeffrey Gillis-Davis, Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

In just under 14 Earth days, Chandrayaan-3 provided scientists with valuable new data and further inspiration to explore the Moon. And the Indian Space Research Organization has shared these initial results with the world.

While the data from Chandrayaan-3’s rover, named Pragyan, or “wisdom” in Sanskrit, showed the lunar soil contains expected elements such as iron, titanium, aluminum and calcium, it also showed an unexpected surprise – sulfur.

Planetary scientists like me have known that sulfur exists in lunar rocks and soils, but only at a very low concentration. These new measurements imply there may be a higher sulfur concentration than anticipated.

Pragyan has two instruments that analyze the elemental composition of the soil – an alpha particle X-ray spectrometer and a laser-induced breakdown spectrometer, or LIBS for short. Both of these instruments measured sulfur in the soil near the landing site.

Sulfur in soils near the Moon’s poles might help astronauts live off the land one day, making these measurements an example of science that enables exploration.

Geology of the Moon

There are two main rock types on the Moon’s surface – dark volcanic rock and the brighter highland rock. The brightness difference between these two materials forms the familiar “man in the moon” face or “rabbit picking rice” image to the naked eye.

Scientists measuring lunar rock and soil compositions in labs on Earth have found that materials from the dark volcanic plains tend to have more sulfur than the brighter highlands material.

Sulfur mainly comes from volcanic activity. Rocks deep in the Moon contain sulfur, and when these rocks melt, the sulfur becomes part of the magma. When the melted rock nears the surface, most of the sulfur in the magma becomes a gas that is released along with water vapor and carbon dioxide.

Some of the sulfur does stay in the magma and is retained within the rock after it cools. This process explains why sulfur is primarily associated with the Moon’s dark volcanic rocks.

Chandrayaan-3’s measurements of sulfur in soils are the first to occur on the Moon. The exact amount of sulfur cannot be determined until the data calibration is completed.

The uncalibrated data collected by the LIBS instrument on Pragyan suggests that the Moon’s highland soils near the poles might have a higher sulfur concentration than highland soils from the equator and possibly even higher than the dark volcanic soils.

These initial results give planetary scientists like me who study the Moon new insights into how it works as a geologic system. But we’ll still have to wait and see if the fully calibrated data from the Chandrayaan-3 team confirms an elevated sulfur concentration.

Atmospheric sulfur formation

The measurement of sulfur is interesting to scientists for at least two reasons. First, these findings indicate that the highland soils at the lunar poles could have fundamentally different compositions, compared with highland soils at the lunar equatorial regions. This compositional difference likely comes from the different environmental conditions between the two regions – the poles get less direct sunlight.

Second, these results suggest that there’s somehow more sulfur in the polar regions. Sulfur concentrated here could have formed from the exceedingly thin lunar atmosphere.

The polar regions of the Moon receive less direct sunlight and, as a result, experience extremely low temperatures compared with the rest of the Moon. If the surface temperature falls, below -73 degrees C (-99 degrees F), then sulfur from the lunar atmosphere could collect on the surface in solid form – like frost on a window.

Sulfur at the poles could also have originated from ancient volcanic eruptions occurring on the lunar surface, or from meteorites containing sulfur that struck the surface and vaporized on impact.

Lunar sulfur as a resource

For long-lasting space missions, many agencies have thought about building some sort of base on the Moon. Astronauts and robots could travel from the south pole base to collect, process, store and use naturally occurring materials like sulfur on the Moon – a concept called in-situ resource utilization.

In-situ resource utilization means fewer trips back to Earth to get supplies and more time and energy spent exploring. Using sulfur as a resource, astronauts could build solar cells and batteries that use sulfur, mix up sulfur-based fertilizer and make sulfur-based concrete for construction.

Sulfur-based concrete actually has several benefits compared with the concrete normally used in building projects on Earth.

For one, sulfur-based concrete hardens and becomes strong within hours rather than weeks, and it’s more resistant to wear. It also doesn’t require water in the mixture, so astronauts could save their valuable water for drinking, crafting breathable oxygen and making rocket fuel.

While seven missions are currently operating on or around the Moon, the lunar south pole region hasn’t been studied from the surface before, so Pragyan’s new measurements will help planetary scientists understand the geologic history of the Moon. It’ll also allow lunar scientists like me to ask new questions about how the Moon formed and evolved.

For now, the scientists at Indian Space Research Organization are busy processing and calibrating the data. On the lunar surface, Chandrayaan-3 is hibernating through the two-week-long lunar night, where temperatures will drop to -184 degrees F (-120 degrees C). The night will last until September 22.

There’s no guarantee that the lander component of Chandrayaan-3, called Vikram, or Pragyan will survive the extremely low temperatures, but should Pragyan awaken, scientists can expect more valuable measurements.![]()

Jeffrey Gillis-Davis, Research Professor of Physics, Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What's Your Reaction?