A 149 million-year-old pterosaur is Britain’s largest flying animal – how scientists proved it from a single finger bone

These results reveal it to be the largest British pterosaur yet described, and the second-largest Jurassic pterosaur worldwide

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Scientists have estimated the size of an extinct flying reptile called a pterosaur, based on fragments of a fossil finger bone discovered in southern England in June 2022.

This 149 million-year-old fossil, known as EC K2576 and nicknamed “Abfab” by the researchers, was found in Abingdon, Oxfordshire – and it is fabulous. They have since attempted to work out what type of pterosaur it was – its taxonomy – and how big the animal was.

During the Mesozoic Era, the “age of reptiles” which lasted from 252 to 66 million years ago and which includes the Jurassic period, dinosaurs, pterosaurs and other giant reptiles roamed Earth – with many dwarfing the largest terrestrial animals alive today.

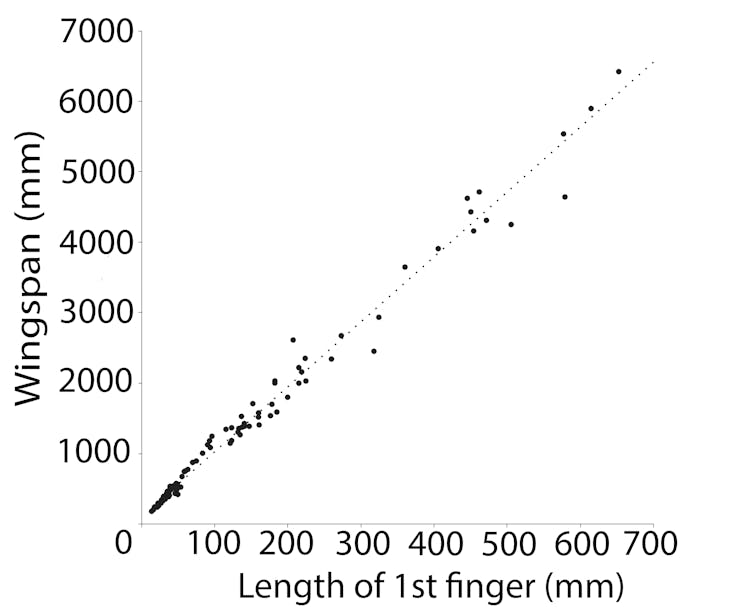

The scientists estimated the body size of this particular species, which has no modern descendants, by collecting data from equivalent fossil bones in more complete fossil pterosaur skeletons for which each animal’s size has been reliably estimated.

They then extrapolated to estimate the wingspan of EC K2576 from its finger bone. The same team of scientists also applied this technique to predict the body size of other pterosaurs, including extrapolating from pterosaur footprints alone.

What were pterosaurs?

More than 110 species of pterosaur have been described. They can be grouped and separated based upon their anatomy – the shape of their bones – which is linked to ecology: where they lived, what they ate and how they behaved. They can also be grouped and separated based on their phylogeny (evolutionary history) and biomechanics (physics of their bodies).

It is not possible to identify EC K2576 to the species level from such limited material. However, by comparing the partial bone against the same skeletal element of other, more complete pterosaur skeletons, the team was able to identify the bone as belonging to a large pterosaur from the group known as the Ctenochasmatoidea. These were similar to pterodactyls, the best known of all the pterosaur groups.

Ctenochasmatoids were mostly aquatic or semi-aquatic pterosaurs. They had a long body with short wing proportions, much like wading shorebirds, and large webbed hindfeet. They were probably not as elegant in flight as other pterosaurs, and they sported a long bony crest on their heads.

All pterosaurs were carnivorous, but within the Ctenochasmatoidea, some specialised by feeding on molluscs (the animal group that includes snails and clams), others were filter-feeders, and some were sweep-feeders (sweeping water with their jaws to catch food), a strategy used by present-day birds such as spoonbills.

Of the pterosaur species that EC K2576 is thought to most closely resemble, Pterodaustro guinazui was a filter-feeder and Ctenochasma elegans was probably a sweep-feeder. So it is possible to infer ecology and behaviour from partial skeletal material.

From a partial finger bone, the scientists estimate the wingspan of EC K2576 to have been between 3.2 and 3.65 metres. This is in the same ballpark as the 3.5m wingspan of the snowy albatross, the biggest living flying bird species, with a wingspan about twice the height of two average humans.

The biggest Jurassic pterosaur based on footprints alone could have been even bigger than that, with a wingspan of up to four metres. The largest known Jurassic pterosaur based on fossils is a specimen belonging to the group Pterodactyloidea that was found in Switzerland and had a wingspan of around five metres.

The paper adds weight to growing evidence that the Jurassic was populated by more large pterosaur species than is thought to have been the case historically.

Pterosaurs have previously been highlighted as an example of Cope’s Rule: that lineages tend to exhibit larger body size over evolutionary time. While the new science behind EC K2576 indicates that Jurassic pterosaurs were larger than we thought, the largest pterosaurs appeared at the end of the Cretaceous, the final period of the Mesozoic Era.

These Cretaceous giants lived between about 77 and 66 million years ago, just before the asteroid that killed off all pterosaurs and non-avian dinosaurs. The pterosaurs Hatzegopteryx and Quetzalcoatlus were the largest living things ever to fly, with wingspans of over ten metres (about six times the height of an average human).

The scientists in the latest study also re-evaluated size estimates of known pterosaurs. This included downsizing one of the most complete Jurassic pterosaurs yet discovered, Dearc sgiathanch from the Isle of Skye in Scotland. Dearc’s wingspan has been revised from around 2.5m to 2.04m. It remains a sizeable animal, similar to a British eagle or swan today.

EC K2576 adds to the growing community of British Jurassic pterosaurs alongside Dearc and the recently described, more modestly sized (1.6m wingspan) Ceoptera, also from Skye.

Why fossils matter

I am an ecologist with a strong interest in anatomy and biomechanics. Bones allow us to infer behaviour via functional anatomy – the shape, size and structure of bones reflects their job. And bones can also inform us about the individual’s life history – for example, via growth and signs of injury and disease.

I have written about inferring parental care in pterosaurs based upon skeletal growth. Occasionally, we get a fossil skeleton that records a particular behaviour – such as a fight, predation, sex, or care of young.

This study is exciting because it applies knowledge and understanding of anatomy and biomechanics to reconstructing elements of morphology (body form and shape) and the life history of an extinct animal.

Extrapolating from isolated bones and fragments can be applied more widely – to reconstruct the size of other extinct animal groups, such as dinosaurs and aquatic reptiles including ichthyosaurs, mosasaurs and plesiosaurs. Re-imagining extinct ecosystems can help us understand how the world and its ecological communities functioned in the past, and differed from the present.![]()

Jason Gilchrist, Lecturer in the School of Applied Sciences, Edinburgh Napier University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What's Your Reaction?