Newly identified prehistoric pterosaur will help us understand evolution of flying reptiles

When dinosaurs roamed the land, the skies above their heads were filled with a variety of soaring reptiles, which swept through the air on slender, membranous wings. These animals, pterosaurs, were not dinosaurs but their evolutionary cousins

Estimated reading time: 12 minutes

Elizabeth Martin-Silverstone, University of Bristol and Paul Barrett, Natural History Museum

We’ve just announced the discovery of a new species of pterosaur nearly 15 years after a fossil was found on the Isle of Skye. It is one of the most complete pterosaur fossils to be found in the UK since palaeontologist Mary Anning unearthed the first from the Dorset coast in 1828.

Pterosaurs were the first backboned animals to achieve powered flight (insects got there first). Pterosaur fossils are known worldwide but their remains are rare in comparison to those of their land and water-based relatives. This is due to the fragile nature of their skeletons, which are composed of thin-walled, hollow bones.

Pterosaur fossils are often incomplete, crushed and distorted. A sparse pterosaur record has been harvested from the Jurassic period (200-145 million years ago) and Cretaceous period (145-66 million years ago) rocks of the UK since Anning’s discoveries.

But most of these are limited to a few isolated bones such as Vectidraco, a toothless pterosaur whose fossilised remains were found on the Isle of Wight in 2008 by five-year-old Daisy Morris.

This is where the Isle of Skye comes in. Although Skye is most famous for the ancient volcanic landscapes of the Cuillin Hills mountain range, there are Jurassic-aged rocks around the margins of the island.

Over the past 50 years teams of geologists and palaeontologists have been gradually uncovering more of Skye’s ancient past. This work has accelerated thanks to the new imaging techniques, mainly CT scanning, which make it easier to study these fossils.

Our new pterosaur was found in 2006 by a team of researchers including Paul Barrett in a loose boulder lying on the beach at Cladach a’Glinne, on the edge of a remote bay overshadowed by the Cuillins.

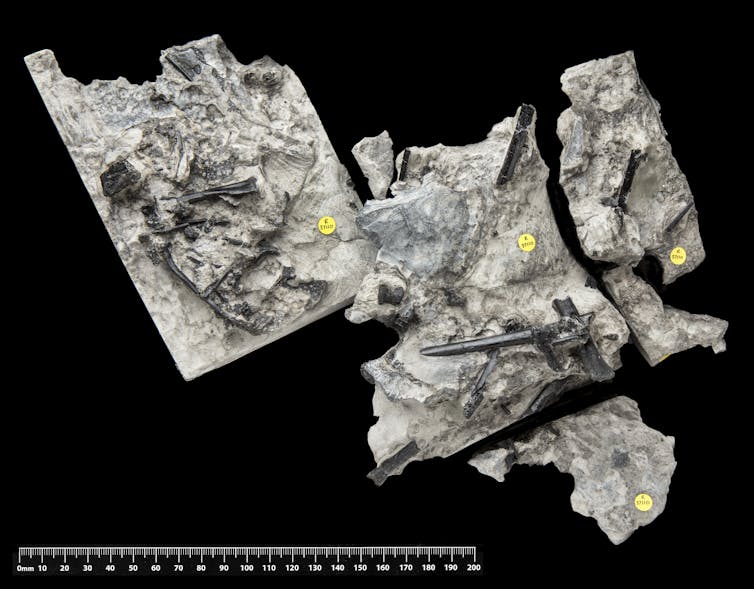

At first sight, the new skeleton was an underwhelming smear of thin, broken, black bone set in a hard, dark-grey mudstone. But, even then, these thin bones suggested that the find would turn out to be interesting.

It took Lu Allington-Jones, one of the Natural History Museum’s fossil technicians, nearly two years to prepare our discovery for study. The rocks from Skye are extremely hard, and the fossil bones are delicate.

Although Lu’s work allowed us to study some of the bones, others remained encased in rock as they were too dainty to remove or expose further.

Once this work was complete, the specimen lay dormant in the museum’s collections for about nine years. But then we decided to examine the fossil using the university’s CT scanner.

Using this equipment, similar to that used in a hospital for diagnosing broken bones, with many months of careful imaging we were able to reveal almost the entire animal in three dimensions.

After comparing it with other pterosaur fossils from around the world, we realised that we were dealing with something new and we called it Ceoptera evansae (from the Gaelic name for Skye, Eilean a’ Cheò, Isle of Mist, and honouring Professor Susan Evans who has worked extensively in the area).

This pterosaur species is important because of the quality of preservation and its age. It is one of only a handful of pterosaur skeletons from the Middle Jurassic period, approximately 167 million years ago.

At this time pterosaurs were undergoing colossal anatomical changes from early small-bodied, long-tailed pterosaurs such as Dimorphodon (roughly the size of a raven) to later pterosaurs like Pteranodon which had a wingspan similar to that of a small airplane.

The lack of good pterosaur specimens from this time interval has hindered scientists’ attempts to understand how pterosaurs evolved from these earlier forms to those that dominated the skies later in Earth’s history. Ceoptera helps to fill this a gap.

For 15 years scientists have studied transitional pterosaurs that show a mix of features seen in the earlier, tailed forms and their later, giant relatives. Ceoptera is one of these transitional forms (called a Darwinopteran), one of the first members of this group known from Europe, and is the second-oldest darwinopteran worldwide.

This makes Ceoptera crucial in understanding the pace of pterosaur evolution, and it has pushed back the appearance of more advanced pterosaurs to the Early Jurassic period, about 10 million years earlier than previously thought. It brings us one step closer to understanding where and when the more advanced pterosaurs evolved.

Ceoptera‘s discovery shows how palaeontologists are making new discoveries all the time, even in places like the UK - one of the most heavily surveyed places worldwide. It also shows how new technology can is helping to unearth the mysteries of Earth’s ancient past.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.![]()

Elizabeth Martin-Silverstone, Research Assistant in Palaeontology, University of Bristol and Paul Barrett, Individual Merit Researcher, Natural History Museum

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What's Your Reaction?