Scientists discover five new species of black corals living thousands of feet below the ocean surface near the Great Barrier Reef

Using a remote-controlled submarine, my colleagues and I discovered five new species of black corals living as deep as 2,500 feet (760 meters) below the surface in the Great Barrier Reef and Coral Sea off the coast of Australia

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Jeremy Horowitz, Smithsonian Institution

The Research Brief is a short take about interesting academic work.

The big idea

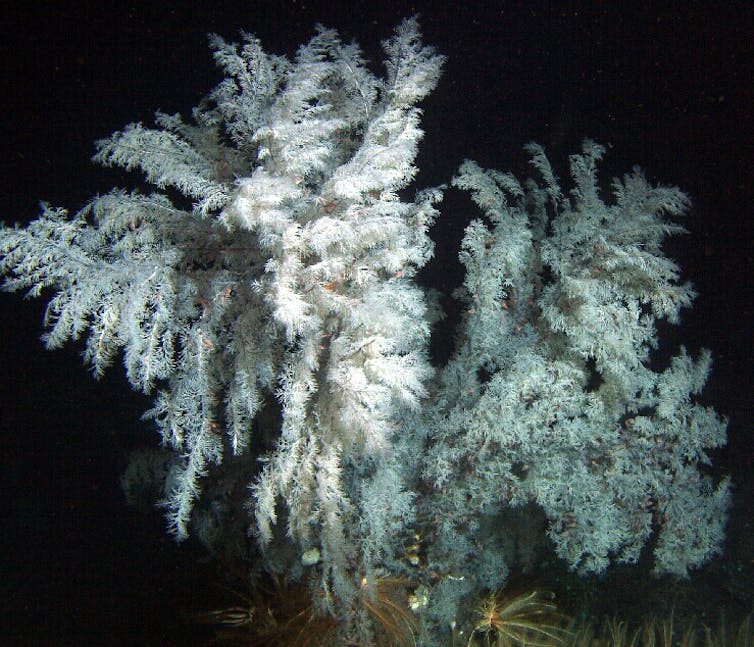

Black corals can be found growing both in shallow waters and down to depths of over 26,000 feet (8,000 meters), and some individual corals can live for over 4,000 years. Many of these corals are branched and look like feathers, fans or bushes, while others are straight like a whip. Unlike their colorful, shallow-water cousins that rely on the sun and photosynthesis for energy, black corals are filter feeders and eat tiny zooplankton that are abundant in deep waters.

In 2019 and 2020, I and a team of Australian scientists used the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s remotely operated vehicle – a submarine named SuBastian – to explore the Great Barrier Reef and Coral Sea. Our goal was to collect samples of coral species living in waters from 130 feet to 6,000 feet (40 meters to 1,800 meters) deep. In the past, corals from the deep parts of this region were collected using dredging and trawling methods that would often destroy the corals.

Our two expeditions were the first to send a robot down to these particular deep-water ecosystems, allowing our team to actually see and safely collect deep sea corals in their natural habitats. Over the course of 31 dives, my colleagues and I collected 60 black coral specimens. We would carefully remove the corals from the sandy floor or coral wall using the rover’s robotic claws, place the corals in a pressurized, temperature-controlled storage box and then bring them up to the surface. We would then examine the physical features of the corals and sequence their DNA.

Among the many interesting specimens were five new species – including one we found growing on the shell of a nautilus more than 2,500 feet (760 meters) below the ocean’s surface.

Why it matters

Similarly to shallow-water corals that build colorful reefs full of fish, black corals act as important habitats where fish and invertebrates feed and hide from predators in what is otherwise a mostly barren sea floor. For example, a single black coral colony researchers collected in 2005 off the coast of California was home to 2,554 individual invertebrates.

Recent research has begun to paint a picture of a deep sea that contains far more species than biologists previously thought. Considering there are only 300 known species of black corals in the world, finding five new species in one general location was very surprising and exciting for our team. Many black corals are threatened by illegal harvesting for jewelry. In order to pursue smart conservation of these fascinating and hard-to-reach habitats, it is important for researchers to know what species live at these depths and the geographic ranges of individual species.

What still isn’t known

Every time scientists explore the deep sea, they discover new species. Simply exploring more is the best thing researchers can do to fill in knowledge gaps about what species live there and how they are distributed.

Because so few specimens of deep-sea black corals have been collected, and so many undiscovered species are likely still out there, there is also a lot to learn about the evolutionary tree of corals. The more species that biologists discover, the better we will be able to understand their evolutionary history – including how they have survived at least four mass extinction events.

What’s next

The next step for my colleagues and me is to continue to explore the ocean’s seafloor. Researchers have yet to collect DNA from most of the known species of black corals. In future expeditions, my colleagues and I plan to return to other deep reefs in the Great Barrier Reef and Coral Sea to continue to learn more about and better protect these habitats.![]()

Jeremy Horowitz, Post-doctoral Fellow in Invertebrate Zoology, Smithsonian Institution

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What's Your Reaction?