There is no one Islamic interpretation on ethics of abortion, but the belief in God’s mercy and compassion is a crucial part of any consideration

As a scholar of Islamic ethics, I’m often asked, “What does Islam say about abortion?”

Estimated reading time: 12 minutes

Zahra Ayubi, Dartmouth College

– a question that has become even more salient since the U.S. Supreme Court reversed 50 years of constitutional protection for the right to get an abortion in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling on June 24, 2022.

This question really needs to be reframed, because it implies a singular view. Islam isn’t monolithic, and there is no single Islamic attitude about abortion. The answer to the question depends on what kinds of Islamic sources, scriptural, legal or ethical, are applied to this contemporary issue by people of varying levels of authority, expertise or religious observance.

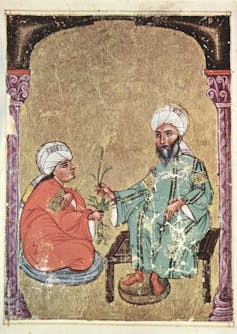

Muslims have had a long-standing, rich relationship with science, and specifically, the practice of medicine. This has yielded multiple interpretations of right and wrong when it comes to the body, including ideas about and practices surrounding pregnancy.

Islamic frameworks for thinking about abortion

The typical framing of the question of whether abortion ought to be legal hinges upon American Christian debates about when life begins. Muslims who get abortions don’t always ask “when does life begin?” to ascertain Islamic positions on the matter. Rather, as my research in the Abortion and Religion project and forthcoming book “Women as Humans” has found, Muslims who get abortions generally consider under what circumstances abortion would be permitted in the Islamic tradition.

Further, the Quranic verses and hadith – recorded sayings of the Prophet Muhammad – are not about abortion per se, nor the moment when life begins or whether abortion is akin to taking a life. Instead, they are descriptions for people to reflect on God’s miracle of what happens in the womb, or rahm in Arabic, which is part of God’s mercy and compassion.

It is often a deeply theological discussion about human actions in context of God’s will, omnipotence and omniscience when it comes to life and death. The dialogue often yields answers that are specific to the person’s cosmic and religious beliefs about God’s nature and mercy and their circumstances in the abortion decision-making process

Many contemporary Muslim jurists and bioethicists point to specific verses in the Quran as well as hadiths with descriptions of the stages of human gestation that are mapped onto the pregnancy timeline in the contemporary abortion debate. The often-cited Quranic verses are 23:12-14: “And indeed We created humankind from an essence of clay. Then We placed him as a sperm-drop in a resting place firm; then We created the sperm-drop into a clinging substance, then We created the clinging substance into an embryonic lump, then We created from the embryonic lump bones, then We clothed the bones with flesh, then We produced it as another creation. So blessed is God, the best of creators.”

Then there is the hadith in which Prophet Muhammad describes what happens in the womb: “The human being is brought together in the mother’s womb for forty days in the form of a drop of fluid, and then becomes a clot of thick blood for a similar period, and then a piece of flesh for a similar period. … Then the soul is breathed into him. …”

These scriptural traditions divide the pregnancy timeline into stages. Muslim jurists consider the 120-day mark of ensoulment (40 days x 3 stages), when God is believed to blow life into the fetus, as the point at which the fetus becomes a legal entity with financial rights. The fetus is believed to have inheritance rights; it can leave an inheritance to its siblings or other kin if it dies, or provide its parents with blood money in the event of a violent action against the mother.

While reference to the scriptural tradition might be enough for many Muslims, some might look to the Muslim legal tradition for precedence. Premodern jurists’ inquiries into stage of pregnancy were mainly to settle questions such as what inheritance laws might come into effect in the event of fetal death. They weren’t asking when life begins to settle abortion questions. And even as they touched on the question of legal personhood of a fetus, they ruled on a case-by-case basis rather than through blanket pronouncements.

Contemporary jurisprudence

Most Muslim jurists and bioethicists today argue that abortion before 120 days of pregnancy is permissible on certain grounds and after this term in cases of mortal danger to the mother. When it comes to abortion, the Islamic legal principle of preservation of life is universally interpreted to mean the mother’s life. Other grounds for abortion vary depending on school of thought but include health concerns for mother or fetus and sometimes include unintended pregnancy, depending on the circumstances of how the pregnancy came about.

Since maternal health can be a nebulous category, acceptance of mental health reasons for abortion may depend on whether people take mental health itself seriously. Concerns might include the mental capacity of a mother to care for herself or a child, or potential suicidal thoughts that put the mother’s life at risk.

Financial affordability is generally frowned upon as a reason for abortion because God is seen as provider, but still accepted in some schools of thought, as the tradition generally promotes mercy above else.

Regardless of contemporary jurists’ positions on the subject, however, Muslims who pursue abortion often do so based on their broad Islamic understanding of God’s compassion rather than in consultation with religious authorities who might act as gatekeepers.

American Muslims post-Dobbs

Part of Islamic discourse’s nuance about abortion is the result of a long relationship between medicine and Islamic thought. For American Muslims, that history is overshadowed by the U.S. Supreme Court upholding the heavy dominance and influence of one Christian view as the only American view on abortion.

There is often a global assumption, which is held by many Muslims as well, that Muslim rules about gender and women’s rights are stricter than dominant Christian American ones. There have been many problematic comparisons of the Dobbs decision and Sharia. Some have called it “Christian Sharia” to characterize the ruling and abortion bans nationwide as religious, yet in doing so they draw on anti-Muslim sentiment and stereotypes of Islam as uniquely gender oppressive.

When American Muslims themselves mirror evangelical Christian views on abortion, however, it may be a form of virtue signaling or out of ignorance of Muslims’ rich historical relationship with medicine.

Even in so-called religiously conservative Muslim countries, such as Saudi Arabia and Iran, laws on abortion are much more liberal than in U.S. states banning abortion. Legally, not only is the life of the mother always prioritized, but because the idea that ensoulment occurs at 120 days is taken seriously, abortion before that point may, and often does, take place in a variety of circumstances such as rape, serial births, mental health issues, untimeliness of pregnancy, etc.

Many American Muslims are speaking in support of the right to abortion. Organizations such as the American Muslim Bar Association, Heart to Grow and Muslim Advocates have issued statements about abortion in Islam and published information on American Muslims’ rights to abortion. The one prevailing commonality among these and diverging Islamic views on abortion is the Islamic concept of God’s mercy and compassion.

Zahra Ayubi, Associate Professor of Religion, Dartmouth College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What's Your Reaction?